In my previous blog “How to Support Your Immune Health – See What Scientific Research Showed”, I provided scientifically proven strategies to support your immune health, which encompass appropriate diets, nutrition, physical exercise, and other lifestyle choices.

In this blog, let’s dive deeper into the specific aspect of physical exercise.

As shown by numerous scientific studies, it is now well recognized that physical exercise is good for our health while a sedentary lifestyle is detrimental to our health. Studies have shown that regular physical exercise is beneficial for reducing the risks and managing chronic diseases including high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, cancer, osteoporosis and osteopenia, Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Physical exercise also reduces all-cause mortality risk due to chronic diseases.1

Regular exercise also improves immune health, brain health, mental health and sleep, reduces stress, and supports hormonal balance. For more details, please check out my previous blog “Health Benefits of Physical Exercise That May Surprise You”.

More specifically to immune health, one may ask how physical exercise benefits our immune health and what types of exercise are appropriate.

We will first discuss the effects of exercise on immune function and immune health in the next section. This will then be followed by the discussion on what amount and types of exercise are appropriate for immune health, as not all amount/types of exercise are created equal.

Topic List

What Exercise Does to Immune Health?

Short-term Effects of Exercise

Exercse and Aging of Immune Function

What are the Appropriate Amount and Types of Exercise?

Is the More Exercise the Better for Health?

Exercise Guidelines for Immune Health

What Exercise Does to Immune Health?

Physical exercise has both short-term/immediate and long-term beneficial effects on immune function.

In addition, regular physical exercise also slows the age-associated decline of immune function.

Short-term Effects of Exercise

A bout of exercise was found to exert immediate short-term alteration to immune cell distribution in the blood stream and re-deployment to peripheral tissues, as stimulated by the release of adrenaline and stress hormone (cortisol) during exercise. Such redeployment of immune cells is thought to represent a heightened state of immune surveillance and immune regulation.2

A bout of exercise was also shown to improve immune/antibody response to foreign invaders or antigens (e.g. virus, bacteria, etc.).3

A bout of exercise can trigger short-term inflammatory response due to tissue injury and repair. However, regular and long-term physical exercise exerts overall attenuation effects on the inflammatory response, thus promoting an anti-inflammatory environment in the body.4

Long-term Effects of Exercise

Regular or frequent physical exercise also has long-term effects on immune health, by enhancing immune function and response against antigens.2

As discussed above, regular physical exercise promotes an overall anti-inflammatory environment in the body. 4

In addition, exercise induces fat metabolism. Obesity, in particular, visceral fat is a prominent contributor to chronic inflammation, which is a culprit of many chronic degenerative diseases including heart disease, type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease/dementia, certain cancers, etc. Fat metabolism induced by regular exercise thus provides an indirect anti-inflammatory effect.5,6

Both direct and indirect anti-inflammatory effects of regular physical exercise help to reduce the risk of chronic diseases.

Exercise and Aging of Immune Function

Age-associated decline in immune function, referred to as immunosenescence, has been well recognized by scientific research.3

In general, aging is associated with alterations and deregulations to almost all aspects of immune function.3

Some of these deregulations include higher inflammatory activity, poorer immune response to antigens, and altered immune cells (T cells) repertoire whereby there is a lower number of naïve immune cells and higher number of mature late-stage differentiated T cells and senescent/functionally exhausted T cells.3

Immunosenescence is thought to linked to oxidative stress accumulated over a lifetime. Diets that are anti-inflammatory and rich in anti-oxidants have been shown to exhibit anti-immunosenescence effects.3

Obesity can exacerbate or induce early immunosenescence. Obese individuals were found to have greater risk of viral and bacterial infections and associated complications.

Regular physical exercise helps with weight management and regulate fat metabolism to reduce the risk of obesity-associated immunosenescence.3

Regular physical exercise also promotes anti-inflammatory environment in the body and improves immune response to antigens, thus countering the corresponding immune deregulation associated with aging.3

Adequate amount of regular physical exercise was shown to slow the age-associated alteration of T cell repertoire, favoring higher proportion of naïve T cells over mature, functionally exhausted T cells, and improve functional capacity of T cells.3

What are the Appropriate Amount and Types of Exercise?

General Exercise Guidelines

Based on numerous scientific studies, a general guideline of physical activity level to support overall health has been established, as shown in Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.7,8

Similar guideline has also been established by the World Health Organization (WHO) as shown in Global recommendations on physical activity for health.9

According to these guidelines, the recommended amount and types of exercise for adults are:8

- At least 1 to 2 units of the baseline (or minimum) amount of aerobic physical activity per week, wherein 1 unit of baseline amount is equivalent to 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity; or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity.

- 2 or more days a week of muscle-strengthening activities of moderate or greater intensity that involve all major muscle groups.

The intensity level of aerobic physical activity is defined based on MET (Metabolic Equivalent of Task), which is a unit for measuring the energy expenditure or metabolic rate of a specific activity.

A MET is the ratio of the rate of energy expended during an activity to the rate of energy expended at rest. For example, 1 MET is the energy expenditure while at rest. A physical activity with 2 METs expends 2 times the energy used by the body at rest.

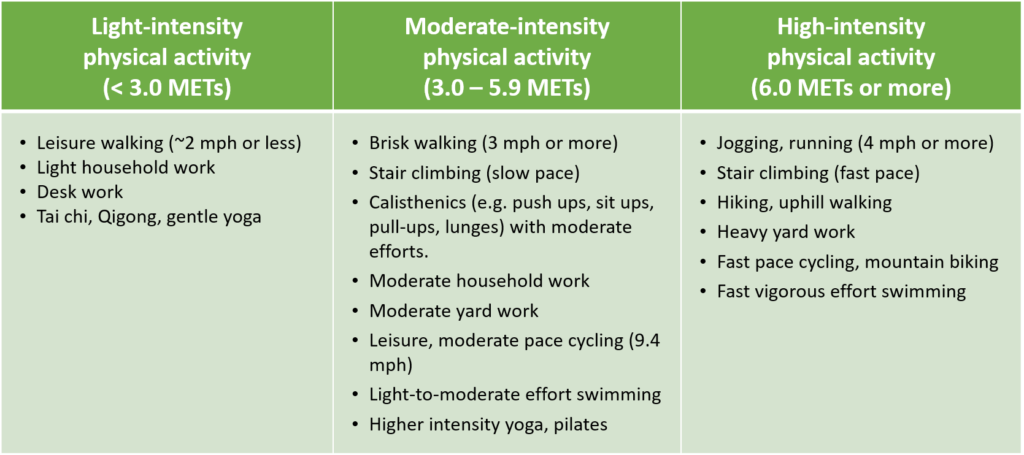

Here is the definition of different aerobic intensity levels:8

- Light-intensity activities are those with less than 3.0 METs.

- Moderate-intensity activities are those with 3.0 to 5.9 METs.

- Vigorous-intensity activities are those with 6.0 METs or more.

Some examples of physical activities associated with different aerobic intensity levels are shown in the Table below. For a comprehensive description of METs associated with different physical activity, please check out the latest Compendium of Physical Activities.

Table 1. Aerobic Intensity Levels of Different Physical Activities

The above guidelines recommend spreading out exercise bouts throughout the week to meet the recommended exercise duration per week.

However, there are studies that showed that individuals who perform their exercise in 1 or 2 sessions per week, e.g. during the weekend (termed the “weekend warriors”), still can get most of the benefits from physical exercise.11

Is the More Exercise the Better for Health?

In general, any exercise is better than none. Even performing physical exercise at a level below the recommended baseline described above can still reduce risk of all-cause mortality.10

Performing exercise at a level more than 2 units of the recommended baseline, i.e. more than 300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity or 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, only provide modest additional benefits in terms of reducing the risk of all-cause mortality. The mortality benefit maxes out at 3 to 5 times the recommended baseline physical activity level.10

Exercise Guidelines for Immune Health

Specifically, on immune health, the above-described general guidelines for physical activity level still hold.

In addition, some studies showed that a bout of long-duration vigorous exercise (e.g., marathon running) and especially if it is unaccustomed, and long-term regular very high-intensity athletic training, especially over-training, are counter-productive to immune health, as such physical activity levels are associated with compromised immune function and higher risk of certain infections and allergies.3,12,13

Long-term very high intensity athletic training, e.g., in the case of endurance athletes, was also shown to have pro-immunosenescence effects, i.e. accelerated age-associated immune deregulation.3,14,15

Note that there are studies that contradict the above findings on negative effects of bouts or regular very high-intensity exercise and training on immune health.2

But in general, it is relatively sound to follow the general guidelines of physical activities, i.e., at least 150 to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, or 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week.3,10

Physical activity level beyond 3 to 5 times the recommended baseline physical activity level likely does not provide additional benefits in terms of immune health and overall health.3,10

Related Articles

How to Support Your Immune Health – See What Scientific Research Showed

Health Benefits of Physical Exercise That May Surprise You

References

- O’Donovan G, Lee IM, Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Association of “Weekend Warrior” and Other Leisure Time Physical Activity Patterns With Risks for All-Cause, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer Mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):335–342. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8014

- Campbell JP, Turner JE. Debunking the Myth of Exercise-Induced Immune Suppression: Redefining the Impact of Exercise on Immunological Health Across the Lifespan. Front Immunol. 2018;9:648. Published 2018 Apr 16. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00648

- Turner JE. Is immunosenescence influenced by our lifetime “dose” of exercise? [published correction appears in Biogerontology. 2016 Aug;17(4):783]. Biogerontology. 2016;17(3):581–602. doi:10.1007/s10522-016-9642-z

- Gjevestad GO, Holven KB, Ulven SM. Effects of Exercise on Gene Expression of Inflammatory Markers in Human Peripheral Blood Cells: A Systematic Review. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2015;9(7):34. doi:10.1007/s12170-015-0463-4

- Walsh NP, Gleeson M, Shephard RJ, et al. Position statement. Part one: Immune function and exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2011;17:6–63.

- Kanneganti TD, Dixit VD. Immunological complications of obesity. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(8):707–712. Published 2012 Jul 19. doi:10.1038/ni.2343

- Department of Health & Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. HHS.gov. https://www.hhs.gov/fitness/be-active/physical-activity-guidelines-for-americans/index.html. Published 2019.

- Department of Health & Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd Health.gov. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf. Published 2019.

- World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Who.int. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/en/. Published 2020.

- Arem H, Moore SC, Patel A, et al. Leisure time physical activity and mortality: a detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):959–967. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0533

- O’Donovan G, Lee IM, Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Association of “Weekend Warrior” and Other Leisure Time Physical Activity Patterns With Risks for All-Cause, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer Mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):335–342. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8014

- Bonini M, Gramiccioni C, Fioretti D, et al. Asthma, allergy and the Olympics: a 12-year survey in elite athletes. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15(2):184–192. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000149

- Meeusen R, Duclos M, Foster C, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(1):186–205. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318279a10a

- Moro-García MA, Fernández-García B, Echeverría A, et al. Frequent participation in high volume exercise throughout life is associated with a more differentiated adaptive immune response. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;39:61–74. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2013.12.014

- Prieto-Hinojosa A, Knight A, Compton C, Gleeson M, Travers PJ. Reduced thymic output in elite athletes. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;39:75–79. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2014.01.004