Diet and nutrition play important roles in the regulation of estrogen and progesterone, two major female sex hormones.

The balance of these two hormones play vital roles to many aspects of women’s health, not just reproductive health.

There are two main manifestations of imbalance between estrogen and progesterone, namely

- Estrogen excess or dominance (i.e., high estrogen-to-progesterone ratio)

- Estrogen deficiency.

These manifestations can result in many disorders and health challenges.

See Female Hormonal Health: The Fine Balance for more details on the contributing factors and health disorders associated with estrogen-progesterone imbalance.

Diet and Nutrition for Estrogen Excess/Dominance

Key factors contributing to estrogen excess/dominance include (see details in Female Hormonal Health: The Fine Balance):

- Xenoestrogen exposure

- Ineffective clearance of excess estrogen in the body

- High levels of unbound/bioavailable estrogen in the blood

- Chronic inflammation

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- Stress

Many of these factors are modifiable and can be mitigated through dietary choices and the intake of certain nutritional compounds as described below.

Minimize/Reduce Exposure to Xenoestrogens

Xenoestrogens are externally present or foreign compounds that exert estrogenic effects in the body and has been shown to contribute to estrogen excess/dominance and detrimental health effects1.

Xenoestrogens can be synthetic or natural occurring substances.

Synthetic xenoestrogens are widely used industrial chemicals including parabens, phthalates, nitro musks, benzophenones, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs), bisphenol A (BPA), pesticides, fungicides and fire retardants that are often found in environmental pollutants, food additives and preservatives, personal care and cosmetic products, and household consumables.

Naturally occurring estrogen is found in plants (i.e., phytoestrogens) and in animal meat products and dairy products. Meat and dairy consumption have been found to raise the estrogen levels in blood and urine.

Exposure to xenoestrogen through foods can be minimized or reduced by the following steps:

- Consume organic foods and food products as much as possible to avoid pesticides, fungicides and herbicides.

- Consume a whole food diet, i.e., avoiding processed foods to minimize exposure to food chemicals including additives and preservatives.

- Consume a plant-rich diet and reduce exposure to hormones found in animal meats and dairy, and industrial pollutants found in fish.

- Drink clean, filtered water.

Promote Clearance of Excess Estrogen From the Body

The liver is the primary detoxification organ in the body responsible for the clearance of excess hormones including estrogen.

Excess estrogen is normally metabolized by the liver into inactive compounds, and then secreted with bile into the small intestine and excreted through bowel movements.

Diet and nutrition can be used to improve detoxification and excretion of excess estrogen:

- Support liver Phase 1 detoxification of excess estrogen by the consumption of cruciferous vegetables which contain a compound called diindolylmethane (DIM).2 Supplementation of DIM can also be used and has been shown to reduce excess estrogen and breast cancer risk factor.3

- Support liver Phase 2 detoxification of excess estrogen by the consumption of cruciferous vegetables, resveratrol (e.g. grapes, blueberries, other berries), citrus fruits and foods that contain D-glutaric acid (e.g. legumes, spinach, carrots, apples, peaches, plums and apricots). A healthy gut flora also promotes liver Phase 2 detoxification. A high-fat diet can suppress Phase 2 detoxification.4

- Support healthy bowel movement with increased dietary fiber intake. Vegetarian diets and diets high in fiber-to-fat ratio were found to reduce estrogen levels and risk of breast cancer.5,6

Suppress Estrogen Biosynthesis

A number of nutritional compounds can inhibit biosynthesis of estrogen. These include vitamin D and phytoestrogens.

Vitamin D

Studies have shown that vitamin D3 supplementation (1000-5000 IU/day) and/or adequate sun (UV-B) exposure to raise the blood serum concentration of calcitriol (active form of vitamin D) to 100-150 nmol/l can support the prevention and management of many types of cancers including estrogen-dependent cancers (breast, ovarian, endometrial and prostate cancers). 7

Note that the recommended Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for vitamin D for adults is 4000 IU/day.

On the other hand, several types of medications can impair vitamin D metabolism, including corticosteroid medications, weight-loss drug orlistat, cholesterol-lowering drug cholestyramine, phenobarbital and phenytoin. 8

Phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens are plant compounds that exert estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects in the body, depending on the target organs/tissues.

Some phytoestrogens including lignans (found in flaxseed), flavonoids (found in berries, parsley, citrus fruits) and isoflavones (found in soy) can regulate estrogen synthesis and actions in the body. 9

Reduce the Levels of Unbound/Bioavailable Estrogen in the Blood

Estrogen is transported in the blood by binding to a protein called the sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG).

Bound estrogen is not bioavailable. Therefore, the lower the SHBG levels, the higher the levels of unbound/bioavailable estrogen and risk of estrogen excess/dominance.

Factors contributing to low SHBG levels include insulin resistance, high blood glucose levels and type 2 diabetes. Dietary approaches that help to mitigate these factors include:

- Plant-rich diets comprise of low glycemic and high-fiber whole fruits and vegetables, legumes, and whole grains; and low in saturated fat and meat (especially red meat and processed meat). 10,11

- Prebiotic and probiotic foods and/or supplementation. 12

- Maintaining healthy weight through adequate diet and physical exercise. 13

Support Adequate Progesterone Levels

Adequate progesterone levels are important to counter-balance the effects of estrogen.

Chastetree (Vitex agnus castus) is a commonly used herbal remedy among Anglo-American and European to manage a number of female reproductive disorders including PMS, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), and menopausal symptoms, by regulating progesterone levels. Clinical studies have verified its efficacy. 14,15

However, it is important to note that some side effects including headache, malaise, gastrointestinal (GI) and abdominal complaints, and skin manifestations have been reported by some study participants.

Reduce inflammation

Chronic inflammation induces biosynthesis of estrogen, while estrogen can exert proinflammatory effects. A vicious cycle can there be formed between estrogen excess/dominance and chronic inflammation.

It is therefore important to mitigate chronic inflammation by reducing exposure to environmental toxins, maintaining healthy weight through adequate diets and physical exercise, and consuming antioxidant-rich whole plant foods.

Avoid Excessive Alcohol Consumption

Alcohol consumption should be limited to no more than 4 glasses of wine per week or no more than 15 g/day of total alcohol. 16,17

Diet and Nutrition for Estrogen Deficiency

Key factors contributing to estrogen deficiency include menopause and exposure to chemicals that inhibit the enzyme, aromatase, responsible for the synthesis of estrogen (see details in Female Hormonal Health: The Fine Balance).

Menopause can be due to normal aging process, ovariectomy or premature ovarian failure. Both estrogen and progesterone are depleted during postmenopause.1

When considering diet and nutrition approaches for estrogen deficiency, it is important to ensure such approaches can counterbalance the deficiency of estrogen while not increasing the risk of pathologies and disorders associated with estrogen excess/dominance. Clinical studies have shown that several nutritional compounds exert such properties as described below.

Phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens exert estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects in the body, depending on the target organs/tissues.

Some phytoestrogens can counter the effects of excess endogenous estrogen in the body, hence are beneficial for addressing estrogen excess/dominance and reducing the risk of disorders associated with estrogen excess/dominance such as breast cancer, ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer.

Some phytoestrogens have protective effects on bone, cardiovascular system and brain/central nervous system, thus are beneficial for reducing the risk of postmenopausal chronic degenerative diseases.

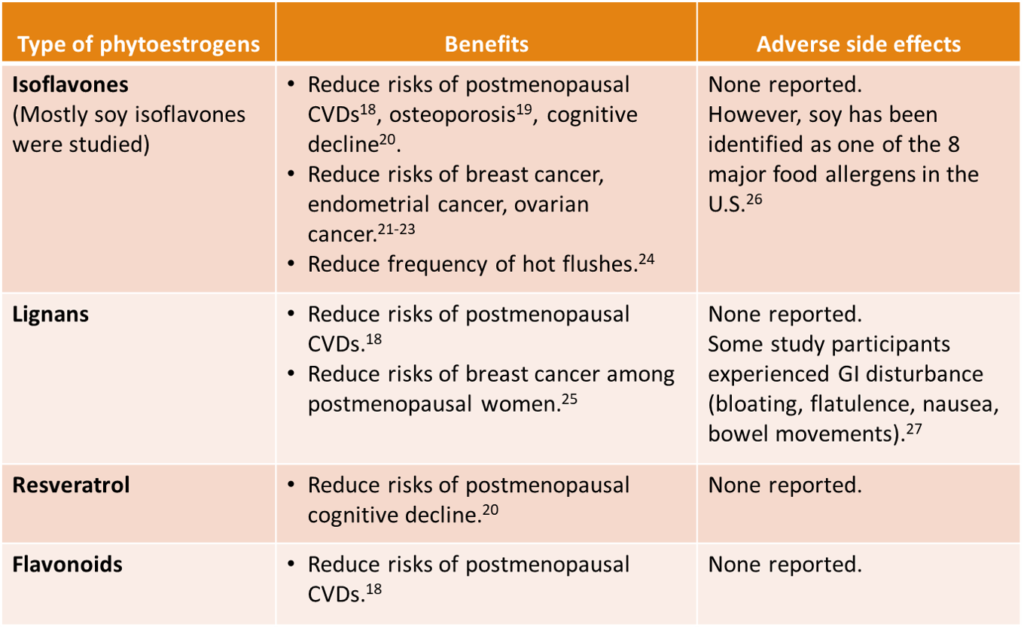

Numerous clinical studies have shown the beneficial effects of the following phytoestrogens:

- Isoflavones (mostly soy isoflavones were studied)

- Lignans (found in flaxseed)

- Resveratrol (found in grapes, berries)

- Flavonoids (found in berries, parsley, citrus fruits)

The benefits of these phytoestrogens are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Benefits of Some Phytoestrogens As Shown in Clinical Studies

Non-phytoestrogens

Maca (Lepidium meyenni) has been traditionally used in the Peruvian Andes for centuries as an adaptogen to address female hormonal imbalance and associated pathologies including infertility, menstrual irregularities and menopausal symptoms.

Maca does not contain phytoestrogens but the compound phytosterols in maca help to regulate estrogen and progesterone levels.29

The number of clinical trials on maca are still limited. However, all the trials have shown that maca supplementation reduced menopausal symptoms among postmenopausal women. 28

No adverse side effects or toxicity were reported in these trials. Different types of maca, characterized by their associated colors, namely “Red”, “Yellow”, “Black” and “Purple”, exhibit different therapeutic properties on female and male reproductive functions. “Yellow” maca was shown to have positive hormone-balancing effect on pre- and post-menopausal women.30

Summary: Overall Diet and Nutrition Recommendation

You can learn more here about how Functional Health Coaching can help you uncover the hidden stressors and the underlying causes contributing to your hormonal imbalance and use holistic diet, nutrition and lifestyle protocol to bring your body back to balance.

Related Articles

Female Hormonal Health: The Fine Balance

References

- Fong M. Female hormonal health: The fine balance. Simply Radiant Living. http://www.simplyradiantliving.com/female-hormonal-health-the-fine-balance/. Published 2018.

- Fowke J, Longcope C, Hebert J. Brassica Vegetable Consumption Shifts Estrogen Metabolism in Healthy Postmenopausal Women. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2000;9(8):773-779.

- Thomson C, Chow H, Wertheim B et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of diindolylmethane for breast cancer biomarker modulation in patients taking tamoxifen. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;165(1):97-107. doi:10.1007/s10549-017-4292-7

- Hodges R, Minich D. Modulation of Metabolic Detoxification Pathways Using Foods and Food-Derived Components: A Scientific Review with Clinical Application. J Nutr Metab. 2015;2015:1-23. doi:10.1155/2015/760689

- Aubertin-Leheudre M, Hämäläinen E, Adlercreutz H. Diets and Hormonal Levels in Postmenopausal Women With or Without Breast Cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63(4):514-524. doi:10.1080/01635581.2011.538487

- Chen S, Chen Y, Ma S et al. Dietary fibre intake and risk of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Oncotarget. 2016;7(49). doi:10.18632/oncotarget.13140

- Grant W. A Review of the Evidence Supporting the Vitamin D-Cancer Prevention Hypothesis in 2017. Anticancer Res. 2017;38(2). doi:10.21873/anticanres.12331

- National Institute of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Vitamin D: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. Ods.od.nih.gov. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/#en1. Published 2018.

- Lephart E. Modulation of Aromatase by Phytoestrogens. Enzyme Res. 2015;2015:1-11. doi:10.1155/2015/594656

- Khazrai Y, Defeudis G, Pozzilli P. Effect of diet on type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2014;30(S1):24–33. doi:10.1002/dmrr.2515

- Mari-Sanchis A, Gea A, Basterra-Gortari F et al. Meat consumption and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the SUN Project: A highly educated middle-class population. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0157990. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157990

- Han J, Lin H. Intestinal microbiota and type 2 diabetes: From mechanism insights to therapeutic perspective. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG. 2014;20(47):17737–17745. http://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17737

- Altaf Q, Barnett A, Tahrani A. Novel therapeutics for type 2 diabetes: Insulin resistance. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2014;17(4):319–334. doi:10.1111/dom.12400

- Cerqueira R, Frey B, Leclerc E, Brietzke E. Vitex agnus castus for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(6):713-719. doi:10.1007/s00737-017-0791-0

- Hajirahimkhan A, Dietz B, Bolton J. Botanical Modulation of Menopausal Symptoms: Mechanisms of Action?. Planta Med. 2013;79(07):538-553. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1328187

- Hartman T, Sisti J, Hankinson S et al. Alcohol Consumption and Urinary Estrogens and Estrogen Metabolites in Premenopausal Women. Hormones and Cancer. 2016;7(1):65-74. doi:10.1007/s12672-015-0249-7

- Playdon M, Coburn S, Moore S et al. Alcohol and oestrogen metabolites in postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Br J Cancer. 2017;118(3):448-457. doi:10.1038/bjc.2017.419

- Gencel V, Benjamin M, Bahou S, Khalil R. Vascular Effects of Phytoestrogens and Alternative Menopausal Hormone Therapy in Cardiovascular Disease. Mini-Reviews In Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;12(2):149-174. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/138955712798995020

- Wei P, Liu M, Chen Y, Chen D. Systematic review of soy isoflavone supplements on osteoporosis in women. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5(3):243-248. doi:10.1016/s1995-7645(12)60033-9

- Thaung Zaw J, Howe P, Wong R. Does phytoestrogen supplementation improve cognition in humans? A systematic review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1403(1):150-163. doi:10.1111/nyas.13459

- Fritz H, Seely D, Flower G et al. Soy, Red Clover, and Isoflavones and Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e81968. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081968

- Myung S, Ju W, Choi H, Kim S. Soy intake and risk of endocrine-related gynaecological cancer: a meta-analysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2009;116(13):1697-1705. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02322.x

- Zhang G, Chen J, Liu Q, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Zhao Y. Soy Intake Is Associated With Lower Endometrial Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(50):e2281. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000002281

- Chen M, Lin C, Liu C. Efficacy of phytoestrogens for menopausal symptoms: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Climacteric. 2015;18(2):260–269. http://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2014.966241

- Calado A, Neves P, Santos T, Ravasco P. The Effect of Flaxseed in Breast Cancer: A Literature Review. Front Nutr. 2018;5. doi:10.3389/fnut.2018.00004

- S. Food & Drug Administration. Food Allergies: What You Need to Know. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/FoodAllergens/ucm079311.htm. Published 2017.

- Flower G, Fritz H, Balneaves L et al. Flax and Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Integr Cancer Ther. 2013;13(3):181-192. doi:10.1177/1534735413502076

- Lee M, Shin B, Yang E, Lim H, Ernst E. Maca (Lepidium meyenii) for treatment of menopausal symptoms: A systematic review. Maturitas. 2011;70(3):227-233. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.07.017

- Meissner H, Mscisz A, Reich-Bilinska H et al. Hormone-Balancing Effect of Pre-Gelatinized Organic Maca (Lepidium peruvianum Chacon): (III) Clinical responses of early-postmenopausal women to Maca in double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover configuration, outpatient study. Int J Biomed Sci. 2006;2(4):375–394.

- Meissner HO, Mscisz A, Baraniak M, Piatkowska E, Pisulewski P, Mrozikiewicz M, Bobkiewicz-Kozlowska T. Peruvian Maca (Lepidium peruvianum) – III: The Effects of Cultivation Altitude on Phytochemical and Genetic Differences in the Four Prime Maca Phenotypes. Int J Biomed Sci. 2017;13(2):58-73.